The first rule of riding in Africa is that you don’t ride at night. Dead animals on the road, live animals on the road, gigantic pot holes, and invisible people walking along the side all become substantially more hazardous after dark. These were the things I thought about as we hurtled through the darkness from Tangier towards Rabat.

In Granada, I’d met up with a British rider named Jonathan who accompanied me to Algeciras where we boarded the ferry to cross the strait of Gibraltar for our first steps onto African soil that night. Jonathan is riding the most kitted out overland bike I’ve ever seen: a brand new KTM 690 Super Enduro with a full fairing, 3 auxiliary tanks, custom made stainless steel crash bars and back rack, bash plate that holds a plastic tank with a spare 2 liters of oil, custom made gps and Go-Pro camera mounts and plenty of other fancy bits. He made most of the custom stuff himself, making it a one-of a kind bike. The thing literally looks like you could run the Dakar Rally on it. And win. The KTM generates 66 horsepower and weighs less than my DR650 which supposedly makes 43 horsepower measured at the crank. The price for all of this performance is the added complexity of a highly tuned engine, fuel pump, fuel injection system, and liquid cooling system, all of which are potential failure points on a long journey. However, with all of those extra horses, he flogs me at any race away from an intersection or up a twisty grade.

Arrival in Tangier took some time, as there were things to do and forms to fill out that no one actually tells you about, but can cause problems and you progress through the arrival and customs proceedures. By the time we started moving, the sun was setting but we were excited to be finally in Africa and keen to make some miles south. Since we knew that we’d need to be in Rabat as early as possible in the morning to get to the Mauritanian embassy to procure our visas, and with no better options in mind, we just kept riding well after night fell.

Upon entering Rabat, we were reminded that we’d landed on a different continent where the rules of the road were substantially different or absent entirely. On an uphill curve we were surprised by an explosion of sparks coming down the other side of the roadway as a small motorbike that had lost traction was now careening down the road horizontally with the rider close behind looking like he was doing a backstroke to catch up with the bike. Fair warning. We put our game faces on.

The next morning we managed to get our Mauritanian visas without much trouble other than our pathetic attempts to translate the forms which were only in French and Arabic. Navigating the city streets became more natural after a couple of days. Its as if the city traffic is a living organism to which we are foreign bodies. Our job is to find our niche in this system, to learn to flow towards path of least resistance without reacting to dangerous things constantly happening around us. While it takes time to see, there is some kindness in all of this chaos, with people doing lots of things that seem very rude in a very polite way. While motorists’ apparent degree of faith in the will of Allah is unnerving for a western rider, it gets easier easier when you realize that while Moroccan drivers don’t seem to mind a close calls all the time, no one wants anyone to get hurt. After all, we were surrounded by all walks of Moroccans deftly navigating the same tumultuous scene on mopeds in sandals with no helmets. The preferred approach for the family of thee on a single moped seemed to be to wedge the kid facing backwards between the two parents with little breathing opportunity for the munchkin leaving little arms and legs protruding from either side of a loving mom and dad moped sandwich.

At the Mauritanian embassy we met another British rider, Will, who like Jonathan and I intended to ride the entire west coast down to Cape Town. He was at the opposite end of the performance spectrum from Jonathan, riding a Suzuki 125cc with old canvas army bags as panniers. He was severely underpowered when fully loaded which necessitated staying off any motorways while in Europe. Amongst our company of riders, we represented the range of performance and technology for overland bikes with my DR650 falling in between their two extremes.

The three of us pitched a camp at the beachfront north of Casablanca for a few days talking about gear and chatting with other overland travelers moving this way and that. The dining room consisted of a stack of our spare tires with my surfboard laid across the top as a table.

Some of he travelers we met piloted these big Mercedes Unimog trucks that looked like fully self-contained desert battle cruisers. The consensus amongst the Unimog folks seemed to be that I wasn’t taking this crossing the Sahara business seriously enough. They would exclaim, “For God’s sake, you’ve got a bloody surfboard attached to your bike!”. I usually just asked where theirs was. Of all things, to be caught in the middle of the Sahara Desert without your surfboard!

There were some mapped surf spots just near our camp and I set out to have a sniff of what was in the water. Though the blue water and rocky headlands looked inviting, these are early days for the surf season here and there just wasn’t much swell moving through.

Jonathan, having nearly already burned through a rear tire, collected a new set in Casablanca that had been transported down by other travelers in a Land Rover from Europe. With his already overloaded bike and the new set of tires strapped to the top, the load now nearly overpowered his side stand so that he would have to park his bike ever so gingerly whenever we stopped to keep it upright.

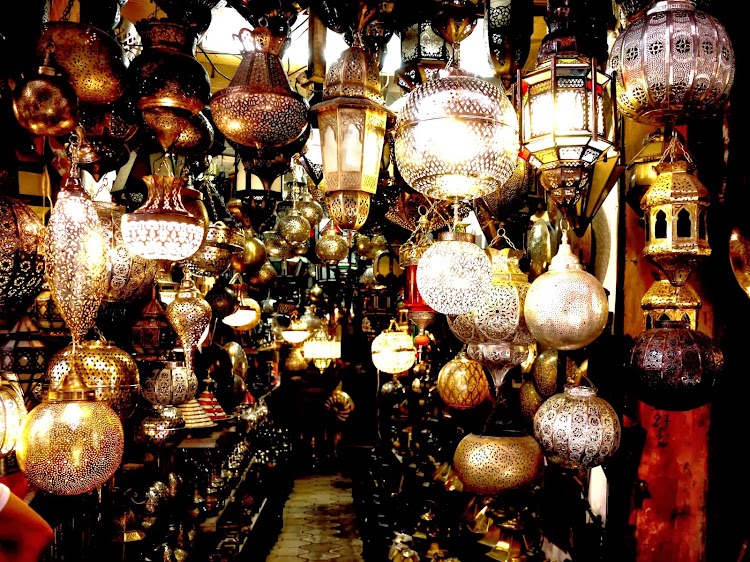

Jonathan and I rode south to Marrakech to collect his Carnet du Passage en Duane (temporary import document for the bike) and meet up with some other riders who had been there for some time already dealing with some debacle in receiving the documents. We stayed in the heart of the walled center portion of the city called the Medina, navigating the labyrinth of narrow streets. We visited the Souk, the local daily marketplace, to take in the sights, sounds, and smells of the place. The Souk is filled with people bustling about their daily business, hawking wares or food, haggling, arguing, or shepherding their families along through it all. In the Medina, you feel the soul and light of the place in the very corridors through which you walk.

The fact that you meet and befriend so many travelers just amazes me.It seems the wanderlust folks have a kinship we can all learn from.